Tilo Baumgartel is a German figurative and narrative painter with a sloping, organic style that I deeply enjoy. Like me he was inspired by comic book artists and old narrative painters like William Hogarth to make artworks that tell a story, in his case, open-ended and apocalyptic fairytales. The atmosphere of his paintings are often strange, quiet, and surreal, often with a foreboding end-of-the-world vibe.

|

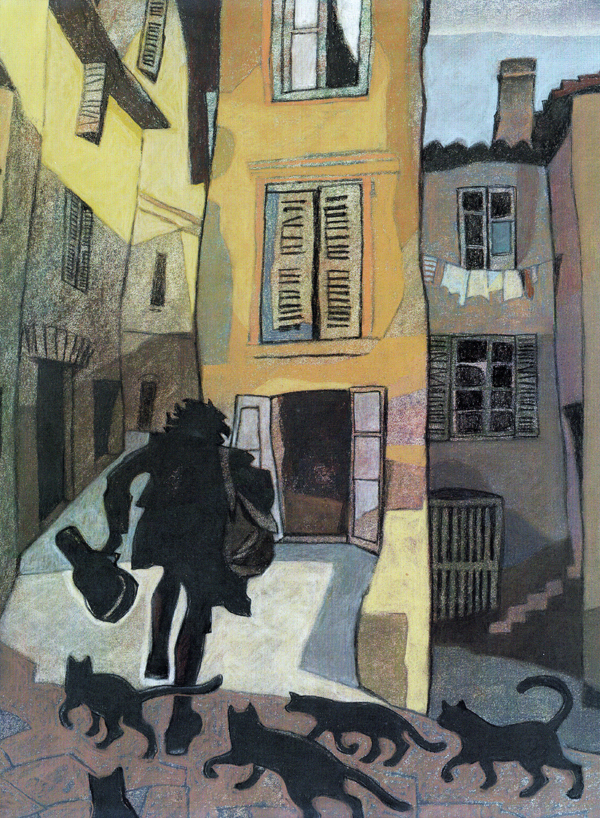

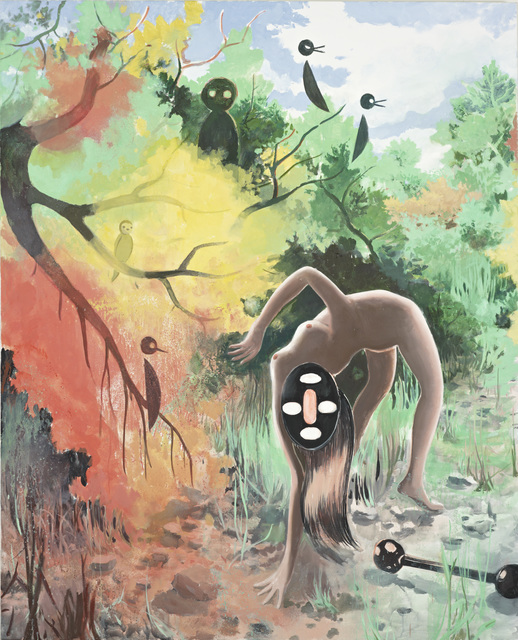

| Patron, 2012 |

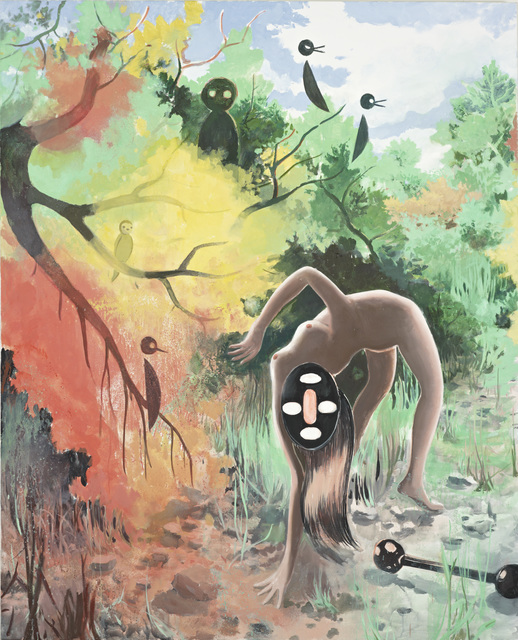

Baumgartel's characters often look very at-home in their strange environments; comfortable, undisturbed, and even apathetic to the weird activities and architecture around them. This contributes to the surreal atmosphere embraced by his toxic pastel color palette.

Though the artist believes that the multilayered complexity of dreams can't be replicated in painting (only film), he does strives for its likeness "What I am able to do... is borrow the atmosphere of dreams, but with a completely different plot and characters."

But Baumgartel also aims for drama and "unstable energy" in his work, which is more often captured in odd acrobatic poses with strong silhouettes than in his gentle brushstrokes.

|

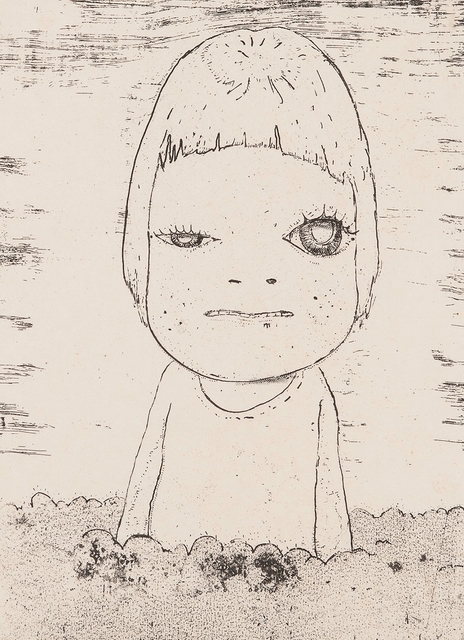

| Untitled, 2011 |

Perhaps the originality of Baumgartel's paintings can be attributed to the stream-of-consciousness process behind their creation.

"I go to the studio, sit down at the table and start drawing. I give myself over to drawing, without any rational thought. And at that moment, perhaps, the material for the next painting is created. Sometimes an idea forms while I'm waiting at a red light, and I try to sketch it out that evening. I think that's what it's like for any artist. If you try to deliberately think up something special, make something interesting – it won't work. The ideas for paintings come about from a string of small chance happenings."

|

| Yoma II, 2014 |

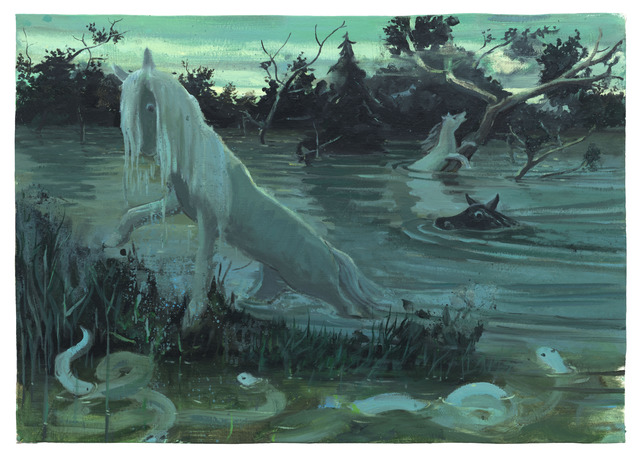

I feel I can relate to the non-academic construction of Baumgartel's compositions, which seem descriptive and narrative but not rigidly planned. He uses slopes and diagonals in many of his works in order to lead the viewer's eye but he doesn't force a strong focal point in the piece, flattening his spaces so that background elements can be appreciated just as much as his central subjects. The chaotic appearance that would normally result from this is resolved by his monochromatic colors and low-contrast value scale.

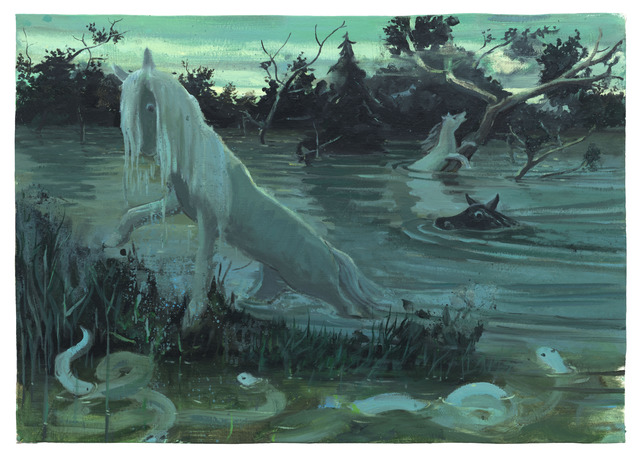

His strongest pieces (in my opinion) are those that captivate you with a stunning subject (the wide-eyed leftmost horse in "Albis") and then surprise you with even more interesting side elements (the snakes and equally terrified expressions of the swimming horses).

|

| Albis |

A final quote from Baumgartel that I found inspiring in its encouragement:

"Every artist should work just for themselves at least in some sort of capacity. The next step is to think about how to set up your life so that you can work without any unnecessary stress and worries about making a living. Perhaps, for some, this means setting aside time for another job on the side. Philip Glass used to drive a taxi, and he composed several of his works while at the wheel. In any case, being a good artist and making lots of money are usually two mutually exclusive things."